Kid Partners in Transportation: Improving Design Outcomes and Community Conversations

By Jen Malzer, M.Sc., P.Eng. and Mariana Brussoni, Ph.D.

Design guides available to today’s transportation professionals are highly sophisticated when it comes to almost all design elements: every truck turn can be sketched, industry accessibility guidelines wrestle through a myriad of competing treatments for different needs, and all land uses have a well-documented trip pattern.

Despite this, transportation design sensitivity seems to stop at children. And though children’s needs are arguably unique and important, many of the fundamentals are non-existent. For example, what is the perception reaction time for a child? Is it faster than a dinosaur’s and slower than a wolf’s? Faced with working with little to no design advice explaining the world from a child’s height and cognition, professionals may instead choose to work with children. Calgary, Alberta, Canada has a few examples of working with small stakeholders that suggest there can be great returns from doing so. This article examines these examples to show the potential of designing for and with kids and argues that engaging children on transportation projects can lead to improved design outcomes and better community conversations.

Kid partners in Calgary

Calgary projects have looked to kids to both gain greater insight and reach a broader community than traditional public engagement. The following are a few examples covering diverse project types and stages that show the benefits to Calgary. Following, we offer useful tools to help practitioners incorporate a child's perspective in planning and design plus insight on why improved design for kids is so critical today in Canada.

Main Street walk audits

The city of Calgary conducted walking and placemaking audits in 2018 to inform main street retrofits and learn about the benefits of different LRT stations activations. The Main Street walk audits were performed using an adapted version of Gehl Institute tools that included more questions around community play and navigation. Local community leaders, Mount Royal University business students, and with two local grade seven classes conducted the measurements over three days. The results were a demonstration of the extent of pedestrian problems to be addressed in the main street reconstruction. More specifically, the audits showed issues with snow removal, accessibility barriers, pedestrian storage issues at intersections, and issues with cars yielding at school crosswalks. These kinds of project data aren’t normally collected—yet they are vital to correct barriers in the pedestrian realm, a fundamental focus of the project. An added benefit was that the youth were a respected voice in the community and helped residents keep the purpose of the project front of mind.

4 Avenue Flyover

In 2017, a community was in touch with the city of Calgary to reimagine the space beneath an inner city flyover that has for decades been a barrier to walking to the downtown and Calgary’s river pathway network. To tackle this unfunded project, University of Calgary Landscape Architecture students were invited to run design charrettes with local grade six students to resolve the space into a community asset. The city of Calgary’s role included hosting public engagement around values and then to vet the students’ temporary and permanent concepts. This approach built enthusiasm in the community and gave hands-on experience to both elementary and university students, while allowing Calgary to enable and listen. The final design, which is now funded, included fun elements for all ages: the elementary students were asked to role play different community members, including thinking about animals and nature. In this project, the kids demonstrated empathy and observation skills needed to design community space.

Erin Woods Traffic Calming

The Erin Woods Traffic Calming project started following a fatal bike collision involving a local teenager. Though the project was important in the media and to community members, public engagement opportunities were not attracting residents: language and time were among the barriers. To overcome these barriers, on-the-street engagement was organized to hear from residents about the new bike lanes that were implemented to narrow the street. The engagement involved closing one side of the road to cars and instead offering: painting within the bike buffer, outdoor games, face painting, community information, and the chance to try wheelchairs or blackout goggles. The event attracted hundreds of community members and also built community capacity and cohesion. Six weeks later the community repeated a similar event on the other side of the street with minimal support from city staff.

Community Leaders

The examples above materialized by reaching out and partnering directly with kids. In these cases, schools and community associations were able to work with city staff to align individual goals to support a collective undertaking. In addition to working with kids directly, reaching out to community leaders. residents, not-for-profits, health care professionals and schools, may also provide you with valuable information on children’s needs. As an example, Calgary is partnering with The Federation of Calgary Communities, Calgary Foundation, and Sustainable Calgary, to deliver a micro-grant program1 to empower residents to use tactical urbanism to enhance pedestrian corridors. This program sees our partners administering the grants and aligning support for communities. Support is funding but also looks like access to university level students to facilitate discussions and capture design ideas. The micro-grant program builds on the success of a playbook of ideas by Sustainable Calgary.2 The playbook was created by partnering with students from a local elementary school and resulted in child-led on-the-ground enhancements of derelict walkways near their school.

An additional benefit of the micro-grant program is the positive and negative feedback provided by residents after having worked with Calgary. The city is acting on this feedback to be a better partner. One of the ways has been to develop a risk booklet that helps city staff to better accept risk and navigate risk truths in their day-to-day work, with the end goal of empowering residents to be community leaders. The risk booklet has been made available through Outdoor Play Canada and here should assist more organizations to consider risk in more fulsome ways.

Excerpt from the Sustainable Calgary #Reimagine Catwalks Playbook.

Another community leader is Vivo, who are expanding their recreational facilities. Through this expansion work they are co-creating programming and moving outside their walls to encourage spontaneous play on community streets and parks. These experiments in play, branded the Gen H Play Project, will soon be paired with a social impact dashboard tracking their population-wide impact in north central Calgary. Individuals and families will be able to see personalized wellness data through a first-of-its-kind app and wearable technology. By partnering with Vivo, Calgary gains insight into what kinds of activations result in measurable differences for residents. This is also an opportunity for Calgary to reinvent its Play Streets application process in a real world scenario with a trusted partner.

Tools and Resources

Adding kid partners to projects means finding genuine ways they can inform and affect project decision making. Engagement specialists are key supports in finding these alignment opportunities. Once these decisions are narrowed down, there are many tools to help guide activities, many of which will be around technical aspects of the project. Here are some tools that are readily available to learn more or start engaging for better designs. The tools are organized around several themes that are pertinent to working with and for kids.

|

Activation |

|

|

Urban design and parks planning tools |

|

|

Risk perception and management |

|

What’s at Stake

Kids are important stakeholders. They inherit the communities designed by today’s professionals and they can offer a kind of empathy and observation that lend to good design for all. And while kids may gladly participate in transportation design, it’s important to remember that their individual potential is also very tied to community design.

Research points us to many urban features that link with positive outcomes for kids: compact urban neighborhoods with traffic calmed streets encourage walking and biking with features such as benches and trees encourage hanging out and chance encounters with friends.4 That said, at a high level, we know that Canadian communities may not be evolving in the ways kids need. In Canada and many other countries, the number of motorized vehicles, a major barrier to children feeling safe playing outside in their communities,5 has more than doubled in the past 30 years.6

As a result, kids are not benefitting from the kind of independent outdoor play that has been linked with positive effects on their physical activity, development, cognitive skills, sense of well-being and resilience, and feeling connected to their community.7 The latest international report cards from the Active Healthy Kids Global Alliance give children around the world low marks on overall physical activity levels.8 A major focus to change this low grade has been looking at ways to encourage children to go outside and play. We’re already seeing the effects of a generation growing up with less time spent playing outside. Helping kids reach their full potential involves all of us working together to help bring children and outdoor play back to our cities and streets. Fortunately, Calgary shows that this may be as easy as professionals literally getting outside to play and be creative with kids.

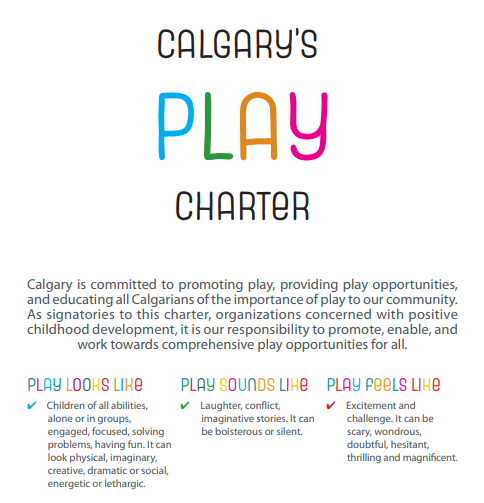

Calgary's Play Charter is owned by community partners committed to

getting more kids playing.

Conclusion

The design and operations of our streets is an important factor in determining how kids use their neighborhoods. Without freedom to travel and play, kids experience serious consequences to their mental and physical well-being.5 Kid-friendly designs and updated transportation guidelines can come about by hearing directly from kids on their ideas for change. Further, partnering with kids in a meaningful way can mean design insight for all users and better community conversations.

In summary, find ways you can collaborate to involve kids in placemaking. Get in touch with progressive community partners, educators, researchers, developers, and especially the kids themselves. Remember that anything to do with children should be fun. Kids are also plentiful and can be locally sourced for your next transportation project. They have helpful insights and can also bridge conversations with the greater community. Consider a local classroom as a “free” sub; you will find their teachers are excited to let you teach for a bit. And the kids? They’ll be thrilled to make a difference in their community and will hardly notice they’re learning via a hands-on, adapted curriculum (math from parking studies or social studies from role-playing different community users). The possibilities are limited only by your imagination.

|

What is play? Research says kids need thrilling play or the opportunity to explore their own limits in terms of: speed, height, getting lost, tools, elements, rough and tumble.9 A child friendly city would have: pop up play opportunities, play streets, chance encounters, flexible or wild spaces, pedestrian priority, and intergenerational spaces. |

References:

- Federation of Calgary Communities. Activate YYC. https://activateyyc.calgarycommunities.com. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- Sustainable Calgary. #Reimagine Catwalks Playbook. http://www.sustainablecalgary.org/publications-1/2019/6/17/reimagine-catwalks-playbook. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- Outdoor Play Canada. Resources. http://www.outdoorplaycanada.ca/resources. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- Lambert, A., Vlaar, J., Herrington, S., & Brussoni, M. (2019). What is the relationship between the neighbourhood built environment and time spent in outdoor play? A systematic review. University of British Columbia.

- Marzi, I., &, Reimers, A., (2018). Children’s independent mobility: Current knowledge, future directions, and public health implications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2441. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112441

- Richmond, S. A., D’Cruz, J., Lokku, A., Macpherson, A., Howard, A., & Macarthur, C. (2016). Trends in unintentional injury mortality in Canadian children 1950-2009 and association with selected population-level interventions. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 107(4–5), e431–e437. http://doi.org/10.17269/CJPH.107.5315

- Cook, A., Whitzman, C., & Tranter, P. (2015). Is ‘Citizen Kid’ an Independent Kid? The Relationship between Children’s Independent Mobility and Active Citizenship. Journal of Urban Design, 20(4), 526–544. http://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1044505

- Active Healthy Kids Global Alliance. The Global Matrix 3.0 On Physical Activity

- For Children and Youth. https://www.activehealthykids.org/global-matrix. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- Brussoni, M., Gibbons, R., Gray, C., Ishikawa, T., Sandseter, E. B. H., Bienenstock, A., … Tremblay, M. S. (2015). What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(6), 6423–6454. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606423.

Jen Malzer, M.Sc., P.Eng. (F) is a transportation engineer for the Liveable Streets division of the City of Calgary, Alberta, Canada where she is currently reimagining Calgary’s traffic calming program to include new design approaches using tactical urbanism principles. In her work she is also pioneering ways to involve more voices in transportation planning like youth, health professionals, and developers by hosting Calgary’s first themed hackathon. Jen is a proud volunteer with ITE and is currently serving as Canadian District Director and co-chair of the Women of ITE subcommittee.

Jen Malzer, M.Sc., P.Eng. (F) is a transportation engineer for the Liveable Streets division of the City of Calgary, Alberta, Canada where she is currently reimagining Calgary’s traffic calming program to include new design approaches using tactical urbanism principles. In her work she is also pioneering ways to involve more voices in transportation planning like youth, health professionals, and developers by hosting Calgary’s first themed hackathon. Jen is a proud volunteer with ITE and is currently serving as Canadian District Director and co-chair of the Women of ITE subcommittee.

Mariana Brussoni, Ph.D. is a developmental psychologist and associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics and the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, Canada. She is an investigator with the British Columbia Children’s Hospital Research Institute and the British Columbia Injury Research and Prevention Unit. Mariana investigates child injury prevention and children’s risky play, focusing on parent and caregiver perceptions of risk, and design of outdoor play-friendly environments. Mariana has published extensively in academic journals and her work is often featured in international media. More details available at https://brussonilab.ca.

Mariana Brussoni, Ph.D. is a developmental psychologist and associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics and the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, Canada. She is an investigator with the British Columbia Children’s Hospital Research Institute and the British Columbia Injury Research and Prevention Unit. Mariana investigates child injury prevention and children’s risky play, focusing on parent and caregiver perceptions of risk, and design of outdoor play-friendly environments. Mariana has published extensively in academic journals and her work is often featured in international media. More details available at https://brussonilab.ca.