Residential Local Street Sidewalk Survey

May 2022 – March 2023 revision

Seeking answers for residential local street sidewalks? This is your resource! We conducted a survey to get answers to some basic questions and summarized what this may mean to you and your community:

Questions:

· Are sidewalks built on both sides of the street?

· Why don’t sidewalks get built with new development?

· Are sidewalks built with in-fill development?

· How do you address gaps in sidewalk networks?

· What size of sidewalk is required?

· What do you make sidewalks out of?

· Are buffer spaces common with residential sidewalks?

· What is allowed on your sidewalk? Chalk? e-scooters?

· What triggers sidewalk maintenance?

· Do you allow sidewalk obstructions?

· What do you mean by obstructions – what does that look like?

· What some best practices others are doing?

· What are some next steps in understanding more about sidewalks?

What does this mean for your community?

· One side or two-sided sidewalks

· Supporting building sidewalks

· Gap filling/fronting sidewalks

Introduction

Many walking trips start on local residential street sidewalks. Yet unlike roads built for cars, these walking networks have many gaps, obstructions, accessibility issues, maintenance oversights, and varying design standards. Sidewalks in residential neighborhoods are an important element of the transportation system that is at times overlooked. Most people like to live in a neighborhood where they and their children have the ability to walk to a neighbor’s house, the park, the grocery store, go for a walk, or simply go to the mailbox. While many standards exist for local residential street sidewalks, today many communities struggle with filling gaps in the walking network and basic design aspects which may in the past been brushed off as details. Maybe the biggest struggle of all is simply having a common understanding of who is responsible for sidewalks. Many times builders struggle with getting the details right in terms of sidewalk widths and obstructions. Successful walking networks get the details right all the time. To this end, there was a need to learn more about what the profession is doing in this specific space - residential local street sidewalks.

Early in 2022, a task force of the ITE Complete Streets Council assembled to improve awareness of the opportunity to achieve best practice in local, residential street sidewalk planning, design, and construction. The group focused upon residential local street sidewalks, understanding that subsequent efforts may be undertaken on collector/arterial sidewalks, business district sidewalks, and trail walkways. All of these are guiding principles of a safe passage. Several priority topic areas identified included the following:

- Who pays and how to fill gaps

- Size

- Obstructions

- ADA

- Sidewalk life

- Maintenance, repairs, and responsibilities

- Driveway and alley

- Code enforcement

- Snow

- Inventories

- Work zones

It was determined that a survey would help establish a baseline of knowledge about these issues. In April 2022 a survey was issued to ITE membership and other transportation professionals. A total of 124 responses were received. The following summary highlights the findings of that survey.

Survey

Two questions provided background related to the employers of the transportation professionals who responded and their level of experience. About 40 percent were municipal employees and about one-third were private (consultant) employees. The respondents had a wide range of expertise with over 75 percent having 10 to 40 years of experience. There also was a wide diversity of geographic representation in the survey responses, covering 44 of the 50 states in the USA and 6 of the provinces in Canada. The greatest number of responses came from Florida (14), California (9) and Illinois (7).

Survey Questions

Q1 - For the jurisdiction you are familiar with, please indicate the role of homeowners, developers, and the agency to the following topics about local residential street sidewalks, to the best of your knowledge:

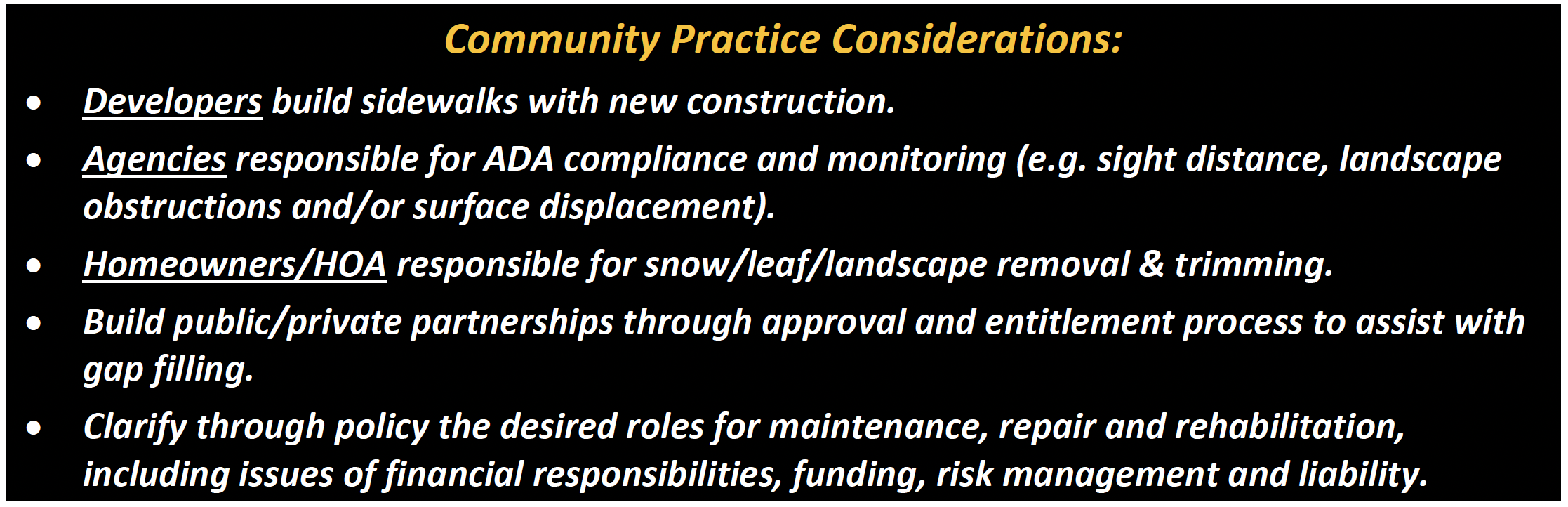

The single greatest takeaway from this question is that agencies were largely responsible for most residential local street sidewalks roles except removing snow/landscaping/leaves (homeowners' role). The only other role where agencies were not the most frequent choice was building new sidewalks (developer role). The second takeaway from this question is that for half of the roles there is a split responsibility where a secondary or tertiary group was identified. This indicates that while agencies are greatly involved, it is not that way everywhere leading to mixed understanding/confusion about expectations as people move between regions. Finally, based upon strength of responses (noted as percentages below) only two roles were clearly agency responsibility (ADA retrofitting and replacing old/end-of-service life sidewalks). In every category there were responses that no one is responsible for these roles indicating a need to consider best practices. This was particularly true for filling gaps in residential sidewalks to adjacent property where right-of-way is not available, as more than a quarter of the responses were "no one is responsible."

|

Roles |

Primary (75%+ response) |

Secondary (50%+ response |

Tertiary (33%+ response) |

|

Building new local residential street sidewalks |

Developer (87%) |

Agency |

|

|

Removing snow, landscape overgrowth or leaves from local residential street sidewalks |

Homeowner (78%) |

|

|

|

Repairing damaged local residential sidewalks |

Agency (83%) |

|

Homeowner (40%) |

|

Maintaining local residential street sidewalks |

|

Agency (71%) |

Homeowner (42%) |

|

Monitoring sidewalk status (for repairs, obstructions, maintenance) |

Agency (80%) |

|

Homeowner (31%) |

|

Filling gaps in residential sidewalks adjacent to property, where right-of-way exists |

Agency (80%) |

|

Developer (42%) |

|

Replacing old/expired/end-of-service-life local residential street sidewalks |

Agency (85%) |

|

|

|

Addressing ADA inconsistencies on existing local residential street sidewalks |

Agency (96%) |

|

|

|

Filling gaps in residential sidewalks adjacent to property, where right-of-way is not available |

|

Agency (60%) |

|

Note: Multiple responses were allowed so totals exceed 100%.

- Repairs are complaint driven – one of the key monitoring mechanisms.

- Sidewalks are not built in new subdivisions due to developers getting exceptions from standards.

- Many times, agencies, developers, homeowners, and elected officials do not know who has responsibility for what.

- Funding for sidewalk repairs seems inadequate.

- Some cities split costs with homeowners on sidewalk repairs.

- Some of the roles are further nuanced by the fact of whether the streets are public or private – which many times subsequent homeowners do not understand.

- The role of homeowner associations (HOA) in sidewalk repair and maintenance should be noted.

- Conflicting understanding of maintenance when potholes in public right of way are repaired by an agency but sidewalks in public right of way sometimes are not – lack of funding plays a key role.

- Even though states may have laws making property owners responsible for adjoining sidewalks, they are rarely enforced.

- Equity should be considered when placing responsibility on homeowners for snow removal, sidewalk repair, and maintenance.

- Gaps are a significant issue and leave the network incomplete for many decades.

- Lack of ADA transition plans highlights a lack of priority for pedestrian networks.

- Most state DOTs do not build/maintain local street sidewalks, so agency means local government.

- Some agencies place full responsibility on property owners for installation, repair, and maintenance of sidewalks. Agency helps with contracts and assesses property owners.

- Some homeowners see public right-of-way where a sidewalk would go as their property.

A second part asked the same question but from the perspective of opinion (feelings or perspective) who SHOULD be responsible for the various roles. The results generally followed the prior question based upon knowledge of current codes, ordinances, and rules. The most significant trend from this question was the uniform increase in what respondents felt should be the agency responsibility for each of the nine roles. The increases ranged from 6 percent on what was already the strongest agency role (ADA, 95 to 101 responses) to a 67 percent increase in the agency role for building sidewalks (which was the lowest response for agency responsibility moving from 12 to 20 responses). All the others increased between 15 and 33 percent. The two roles that had the lowest response (maintaining sidewalks and filling gaps when right of way is not available) both migrated strongly toward agency responsibility in this question. This indicates a potential desire for sidewalk maintenance to be elevated in importance, similar in responsibility as roadway maintenance. Overall, when assessing professional’s opinions regarding responsibilities, seven of the nine were strongly directed to agencies with only the building of sidewalks (developer) and snow/leaf/landscape removal (homeowner/HOA) as roles outside the agency purview.

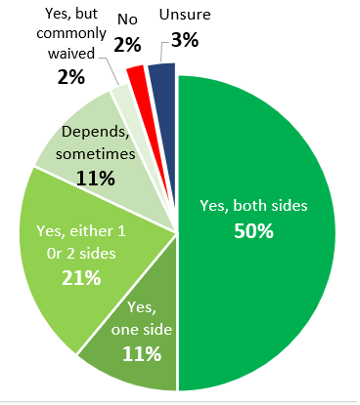

Q2 - For new residential development (subdivisions), are sidewalks required on new streets?

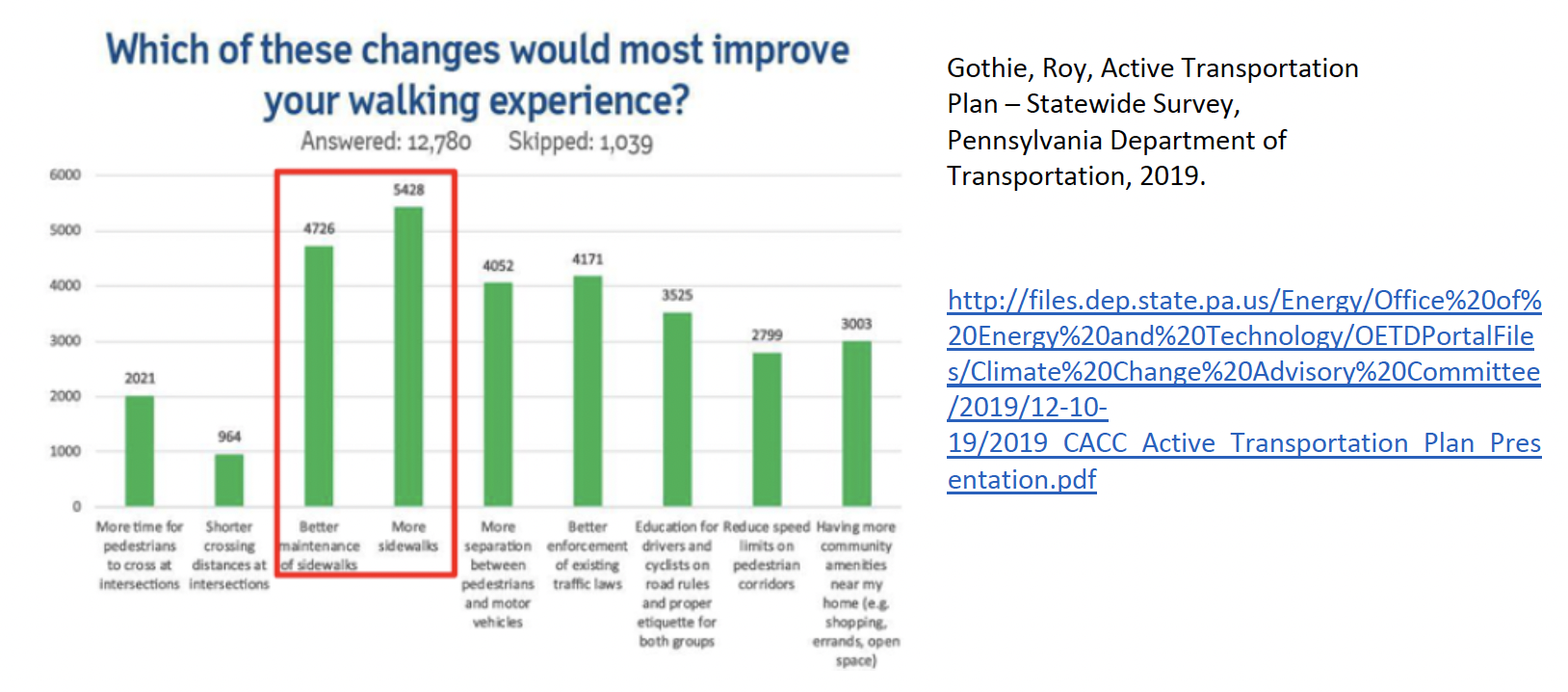

Of the responses, 95 percent require sidewalks. The conditions vary from requiring them on both sides of the street, one side of the street, either one or two sides of the street based on circumstances to more conditional requirements where they are required sometimes or depending upon agency decisions or required and waived based on requests. The strongest response was requiring sidewalks on residential local streets both sides of the roadway (50 percent).

Some of the conditional circumstances were the following:

- Based upon average daily traffic (150 ADT, or about 15 single family dwelling units)

- Both sides in urban areas and one side in rural areas

- Required only when 50 percent of the street already has sidewalks

- Commercial areas required but optional for residential (one or two sides)

- Redevelopment/in-fill/retrofit conditions which advance walkway continuity of at least one-side sidewalk

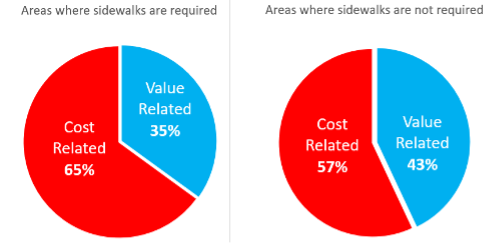

Q3 - What have been the reasons that sidewalks do not get built with new development?

This question delved into why sidewalks do not get built originally as development occurs. Several responses were provided ranging from cost-based reasons (cost and drainage) to value-based reasons (community does not want sidewalks, they were deemed as unimportant, and people can use the street). Respondents were allowed to check as many items as applied in their perspective. The findings provide insight into professionals understanding of why sidewalks do not get built. At the top of the list was cost, followed by an understanding that their community did not want sidewalks.

The question was asked two different ways to understand how the perception changed with context. The condition of sidewalks being required was tested and found to affect the cost v. value-based belief regarding the provision of sidewalks. While cost was always was the top response, when tested with the condition of “required/not required” it exposes an interesting finding where cost is a reduced reason for why sidewalks are not provided and value to the community (value) becomes more important (gravitating from about two-thirds toward one-half). This would lend itself to a legacy belief system among professionals where it is not believed that the public, developers, or decision makers value sidewalks in a way to support and defend their construction as compared to roadways or driveways.

There were 64 comments provided to this question offering comments as to why or why not sidewalks are built. The most common note was related to provisions of sidewalks in urban and or densely populated areas as compared to rural. Most urban responses were that sidewalks are required and not waived. Several responses noted in rural areas that sidewalks are not required on local residential streets. A summary of the comments is provided below:

- Sidewalks not required:

- In rural settings

- Where sidewalks don’t go anywhere/don’t connect anything/gaps

- Where limitations are present due to right-of-way, trees, heritage, natural environment utility, and/or topography issues

- Case law on fronting improvements

- When they take up too much of the development land

- Where not indicated on the General Plan

- Where in lieu fees are accepted

- Sidewalks being delayed following subdivision until houses are actually built, leading to eventual sidewalk waivers by developers because no sidewalks have been built

- Several commenters noted they never waive sidewalks and never have any pushback because of it

The survey exposed a need to improve outreach and understanding of sidewalk value within a community, in a collaborative fashion, to avoid the tensions that are known to exist in some communities when addressing the provision of sidewalks.

Q4 – Fronting improvement: For infill residential development (developing underutilized land with 1 to 5+ dwelling units), are fronting sidewalks required? For major remodeling/renovation of a residential dwelling unit (for instance, $250,000 of work or greater), are fronting sidewalks required if they do not previously exist?

These questions were targeted to understanding provision of sidewalks for infill and renovation circumstances. These are situations where gaps can be filled in the walking network but many times the opportunity is lost through waivers or exceptions. Both questions allowed comments regarding if exceptions were allowed.

More than 91 percent of the respondents require sidewalks with infill development (circumstances where one to five dwelling units are added to previously developed areas using under-utilized land). In nearly 1/3 of these cases, exceptions or waivers are permitted allowing the developer to not provide fronting sidewalks. In the second circumstance (major residential remodeling/renovation), there was a nearly equal (51/49) split between respondents indicating they do or do not require sidewalks in this care. What is different from the “infill” circumstance is the share of “unsure” responses (41 percent). This indicates that using the opportunity of major residential remodeling/renovation to fill gaps in sidewalk networks is not as commonly required or considered, presenting an area for education within the profession.

The comments that respondents provided are highlighted below related to exceptions:

Infill:

- No exceptions

- Local agency makes the determination of waiver (planning department, public works)

- Local agencies are responsible for in-fill sidewalk construction

- Consideration of the “context” of infill is assessed (e.g. reuse of existing buildings)

- Exceptions for:

- Where no other sidewalks are nearby (or less than 50 percent of streets have sidewalks)

- Hills with narrow right-of-way is the only exception

- Extreme drainage issues

- Rural areas

- Short cul-de-sacs

- The act of subdivision as compared to building on a vacant lot not requiring subdivision

Remodel/Renovation:

- For a major remodel or driveway replacement that needs a building permit, a sidewalk is required

- Sidewalk required for:

- Building additions of 100 percent of existing building

- 50 percent of original value

- Exceptions for:

- Rural areas

- Where sidewalks do not already exist

- Inadequate setback

- No “site” work is being done

- Fire teardown

- Short cul-de-sacs

Q5 - How does your jurisdiction address gaps in local residential street sidewalks?

The responses to this question allowed multiple answers and are shown below. There were 29 “other” responses which included specific circumstances that were combined with the listed options.

The jurisdiction in-fills gaps in local residential street sidewalks = 65%

Gaps are not addressed, only require fronting development to provide sidewalks on their property = 44%

When a development is adjacent to a sidewalk gap, the jurisdiction contributes to have the developer fill in the gap at the time of the development = 28%

Transportation impact fees are used for off-site sidewalk gap filling adjacent to a development = 23%

Highlights from the “other” response included various ways/reasons to fill gaps which include the following:

- Gaps less than ¼ mile, developers are required to build an asphalt connection to fill the gap

- Special funds and assessments

- County, regional, and state funds/grants

- In-lieu fees

- Access to transit access

- Street maintenance/repair work

- Safe routes to school

- Commercial development

- Nearby safety issues or senior housing

- City installs and assesses property

- Voter approved bonds

Some agencies have extensive programs for sidewalk development and maintenance[1] and others have little or no program. While the programs do not have to be extensive, agencies need to consider policies for provision of sidewalk networks, who pays and how.

Q6 – Sidewalk Size: In your jurisdiction, what is the required new residential local street sidewalk width? AND in your jurisdiction, what are most of your existing residential local street sidewalk widths?

These two questions were aimed at identifying what respondents know are local requirements for sidewalk width for local residential streets and comparing that with their observation of the inventory of sidewalks in their jurisdiction. What respondents see, what the requirements are, and the what the practical local residential street sidewalk width for mobility are different. The most frequent local residential street requirement was for 5-foot (1.5 m) sidewalks but the most frequently observed condition was 4-foot (1.2 m) sidewalks. Some responses noted that the size depended upon land use type and others noted that the size depended upon if the sidewalk was attached (curb-tight = 6’) or detached (with landscape buffer = 5’).

The survey highlights a legacy of prior design guidance related to sidewalks that equated minimum clearance to sidewalk design width. These are not the same. The observed data exposes this with a large number of 4-foot sidewalks when there is clearly inadequate space for two sidewalk users to pass each other safely without going into the street. For a person with accessibility needs, many times there is no access to the street due to curbs. The following examples show the actual width of sidewalk users. Each of these users require 2 to 3 feet of space. To pass they would require double that space plus shy distance. Minimum 6-foot sidewalks can address these needs. Minimum clearance of an obstruction at a point is different. Based upon the survey, there is a call for agencies to understand their goals for accessibility, safe passage, and pedestrian passing on local residential street sidewalks and consider updating their plans to encourage and promote greater walkability.

Q7 – What is the required surface for local residential sidewalks?

The vast majority of responses to this question were concrete (85 percent). This is similar to prior research[2]. Seven percent allowed options including concrete or asphalt (not specifying either). Another 7 percent required asphalt and 1percent had no requirements. The most significant comment was that when the sidewalk space became more “trail-like” and was 10 or more feet (3 m) wide, asphalt was utilized as a continuation of a shared use pathway. The other common application of asphalt sidewalks was noted for “gap-filling” where an off-site connection could be extended from in-fill development as a more durable form of temporary pathway until permanent off-site improvements were constructed.

There was little to no mention of pavers. Based upon observations of the Task Force where they have been utilized on local, residential streets, many times they encounter issues with ADA and maintenance considerations. This could contribute to why most agencies avoid their use in this application due to poor life cycle performance.

Q8 - For the residential area where you live - does the local residential street have street lighting?

Nearly 90 percent responded that they have street lighting. Given many of the responses are from urban locations, this may vary in non-urbanized areas or where jurisdictions have “dark sky” policies. However, given the large number of pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries that occur during dusk, evening, and night conditions (and its increasing share recently, now over 80 percent dark/dusk)[3], the provision of local residential street lighting is most common. FHWA’s recent pedestrian lighting primer[4] is a resource related to this topic, which references a common lighting standard from IES (RP-8-18)[5]. Both the lighting of sidewalks and pedestrian crossings are important considerations for designers.

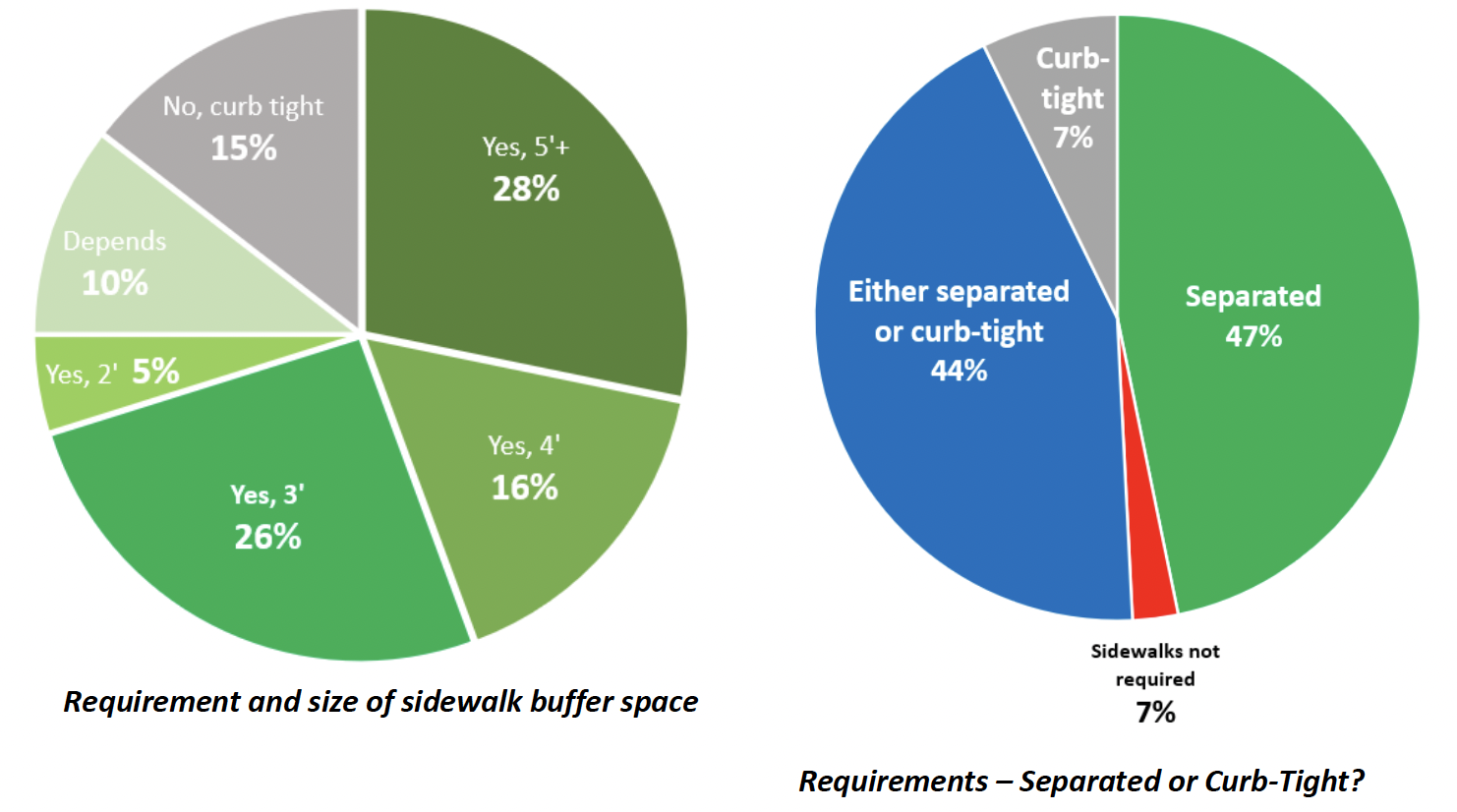

Q9 - Are buffer spaces typically provided between the edge of local residential street sidewalks and back of curb or edge of pavement (i.e., separated, detached, or landscape strip)? AND if a landscape buffer is provided, who controls what is planted in it?

Two questions focused on buffer spaced between the sidewalk and the street. About 75 percent of the responses indicated that a buffer is required. The two most common buffer sizes were 3 feet and 5 feet or greater (1 to 1.5 m). Without at least 3-feet of buffer, it is difficult to grow or maintain landscaping. The buffer accomplishes numerous functions for local residential streets:

- Provides space for street furnishings and utilities (poles, mailboxes, fire hydrants)

- Provides space for landscaping, trees, and low impact development approaches/swales (green streets)

- Improves sight distance at driveways and better corner setback

- Provides space for snow removal/storage

- Greater separation between vehicles and pedestrians

At the same time, nearly an equal number of participants noted that curb-tight or buffered sidewalks are required. As for who controls the maintenance and plantings in a buffer, there was a split right down the middle between the jurisdiction and the homeowner (or abutting property owner/homeowners association). There were about the same amount of curb-tight sidewalk responses as there were to prior questions (about 7 percent). Of the 17 “other” responses, several points were noted including the following:

- Jurisdiction controls tree planting and the homeowners control other landscaping.

- Jurisdiction allows homeowners to have something other than grass from approved listing.

- Jurisdiction retains restrictions on plantings in sight lines.

- Jurisdiction picks initial plantings and then it becomes homeowner responsibility.

- Homeowner plants in buffer but if complaint arises regarding maintenance (overgrown, sight obstructions), jurisdiction enforces.

- Jurisdiction has program for plantings for low-income households.

- Where homeowner’s associations exist, they address issues.

Q10 - Are bicycles, scooters and other micromobility modes permitted to use a local residential street sidewalk? AND is the use of chalking (e.g., hop scotch, art) allowed in your neighborhood on the residential street sidewalks?

The two questions surrounded the use of local residential street sidewalks. The first was to understand if other forms of mobility are allowed to utilize sidewalks (such as bicycles, scooters, or other micromobility modes). The majority allow them on sidewalks while several jurisdictions are still looking into this topic. Some noted it was not an issue and not necessary to allow or prohibit. Some of the comments from “other” responses included the following:

- Children (but not others) are allowed to bike on sidewalks

- Persons with mobility impairment are allowed to use motorized means on sidewalks

- OK to park scooters on sidewalks

- Allowed but not if there is an adjacent bicycle lane/facility

The second question asked about the use of sidewalk chalk on local residential street sidewalks. The overwhelming majority of jurisdictions allow this activity/use.

The survey indicates the desire for residents to be allowed to use local residential street sidewalks in a fashion which encourage their use. Overly prescriptive rules that control use but do not affect safety are to be avoided based upon survey results. Most state’s vehicle codes address the topic of bike/micromobility use on sidewalks and further restrictions would not seem to be necessary.

Q11 - What triggers your jurisdiction to require (or to perform) maintenance/ repair on a local residential street sidewalk?

The most frequent “trigger” was citizen requests or complaints. This points to a very reactionary approach to maintenance and repair. The next two were sidewalk vertical separation and accessibility issues or deficiencies, followed by surface condition disrepair. The lowest response for triggers was blockages. The least frequent response was that local residential street sidewalks are not monitored or repaired. A common response in the other category was that sidewalk repairs and maintenance were connected to other public works activities such as roadway projects or major rehabilitation/renovation.

The real question is how much effort should be expended to proactively address sidewalk maintenance and who should do the monitoring. While some agencies partner with neighborhood groups to support issue identification, other neighborhoods may not have the time or trust to engage the agency in such efforts (a valid equity consideration). Citizens are the eyes on the ground and their input can be not only valuable but cost effective if managed properly. Tools exist for volunteer assistance of neighbors in assessing sidewalks and walkability[6]. Technology is changing that can not only pair citizen input real-time (crowd-sourced data) but also make use of emerging autonomous vehicle sensor/perception device data to document/inventory changes in condition. These approaches in the future may lead to a triple bottom line of greater knowledge of conditions that merit change, low-cost monitoring, and more responsive services to the public.

Q12 - Are your existing local residential sidewalks free of obstructions within the walking zone?

The most common obstructions to local residential street sidewalks are trees/vegetation/landscape, garbage cans and utility vaults/bungalows, utility poles/light poles, parking, and fire hydrants (in that order). Signs and mailboxes are among the least common obstructions – and, so far, electric vehicles charging cables are not an issue (yet). The following figures provide examples of both good path management and poor path management for local residential street sidewalks.

Comments:

- Where brick monument mailboxes are used, sidewalks can be widened behind the mailbox to allow a clear, minimum 5-foot walkway.

- Many obstructions are on 75 (+/-) year old rights-of-way where sidewalk widening is not possible.

- Using buffer spaces for various utilities, poles, garbage cans, snow storage and water quality detention features addresses obstructions and addresses other key needs.

- In-fill development in older neighborhoods with obstructions commonly encounters obstructions and the need for planning for sidewalk clearance needs.

- Multi-family housing may create new needs for electric vehicle charging station placement on-street which raise issues related charging cable crossing sidewalks.

- Conduct a complete inventory of sidewalks before doing anything else (as a part of an asset management system)

Note: With advancing connected and automated vehicles, comprehensive asset inventory and monitoring opportunities may emerge in the next decade for sidewalks that have the potential to eliminate laborious field inspection tasks. It could include automated notification to maintenance staff and homeowners regarding maintenance responsibilities.

- Elevate the importance of sidewalk gap filling by identifying priority segments (rating) as a part of capital improvement project planning.

- Seek funding priority for sidewalk gap filling.

- Locate utilities outside the sidewalk (consider a 1 to 2-foot utility space outside the edge of walk within right-of-way).

- In-lieu fees for sidewalks instead of waiving sidewalk construction in certain circumstances.

- Create a citizen engagement tool (web-based) to help prioritize sidewalk gaps.

- Landscape districts can be set up pay for sidewalk installation and maintenance

- Use Active Transportation and Safe Route to Schools programs to help elevate sidewalk priorities.

- Using a 3m (10 ft) dimensions behind the curb for new developments.

- Providing greater neighborhood connectivity – beyond sidewalks is important.

- Have a 7-year cycle of residential street period inspection. City requests homeowner to repair or reimburse city to repair sidewalks.

- Have grinding/diamond cutting contractors available to remove sidewalk tripping hazards.

- Having routine schedule for monitoring sidewalks maintenance – paving condition before each school year and landscape obstructions at the end of winter and early spring.

- https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike/tools_solve/fhwasa13037/research_report/index.cfm

- https://epd.wisc.edu/tic/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/12/Guide-Maintaining-Pedestrian-Facilities-for-Enhanced-Safety.pdf

- https://www.co.washington.or.us/LUT/Divisions/Operations/roadwaysurfaces/bike-ped-improvements.cfm

- https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/bc652d6cbedf46a491c653b8ec2043af

- https://lawrenceks.org/sidewalk-improvement/

- http://vtrc.virginiadot.org/PubDetails.aspx?PubNo=10-R4

- Neighborhood homeowner’s associations are a good answer to many of these issues.

- Oak trees (and large heritage trees) are wonderful but cause lots of sidewalk problems.

- Widening sidewalks to address electric golf-cart travel may need to be considered in some communities.

- Street sweeping activity may be a means of inventory update.

- https://pub-saskatoon.escribemeetings.com/Meeting.aspx?Id=880a6cf4-614d-4499-88b6-dacca617d048&Agenda=PostMinutes&lang=English&Item=23&Tab=attachments

- State DOTs typically do not install or maintain sidewalks. It is also difficult to respond in a manner that reflects uniform practice as towns, cities, and regions, all can differ. Some municipalities can differ within their borders.

- Utility renovation (such as water lines or storm water enhancements) are opportunities to piggyback sidewalk projects.

- The lighting design requirements are obtained from IES Standard Guidelines.

- Some communities add street lighting on a block-by-block basis through a petition process, requiring 2/3 of property owners agreeing to the request.

Examples of Common Obstructions

Local Residential Street Sidewalks

What Does This Mean for Your Community?

The survey of practices for local residential street sidewalks highlights several areas that communities need to consider regarding current practices as they develop walking networks and pedestrian plans. The following sections follow the order of the survey questions and key local residential street sidewalk topic areas:

- Roles and responsibilities

- Sidewalks on both sides of the street

- Why sidewalks do not get built

- Fronting sidewalks for in-fill and renovation development

- Addressing gaps

- Sidewalk width

- Paving surface

- Buffer areas

- Street lighting

- Triggers for maintenance

- Avoiding obstructions

The task force identified other resources and practice considerations related to local residential street sidewalks. These are offered as suggestions to communities exploring best practices in local residential street sidewalks. Some communities may have addressed many of these considerations and may use this to refine community practices. For others, taking a new look at the topics and determining what works best for your community can contribute to improved walkability, higher walkscores[7], and greater community understanding of sidewalk value.

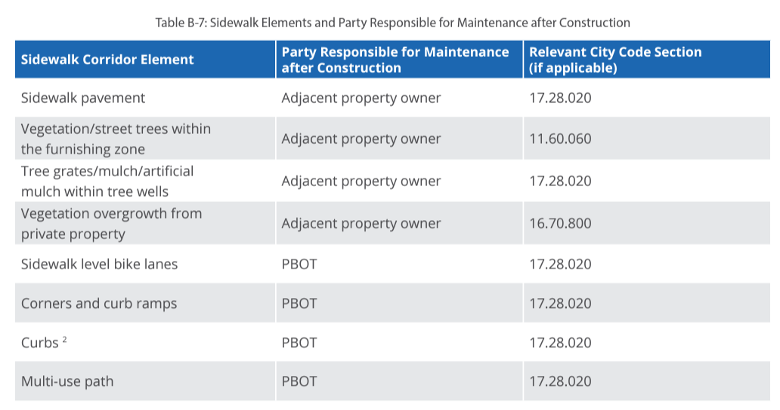

Roles and Responsibility for Sidewalks

For many residents and in many communities this topic is not well understood. There are overlapping areas that can contribute to interpretations, confusion, and lack of transparency. Community choices can increase, reduce< or defer responsibilities for the key parties.

Example: Portland Pedestrian Design Guide, (Portland, OR: Portland Bureau of Transportation, September 2021),48.

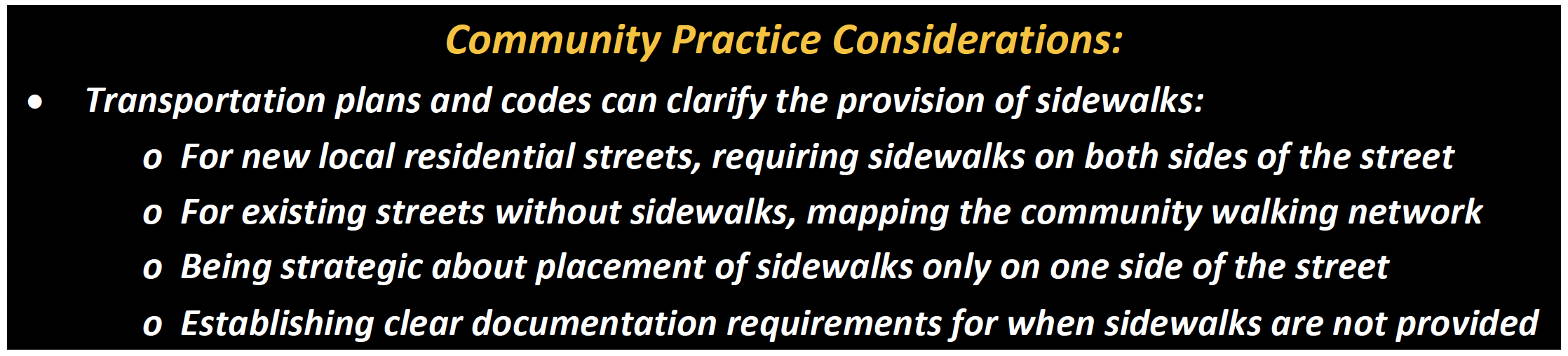

Sidewalks on One or Both Sides of a Local Residential Street

The survey demonstrated that most communities require sidewalks with new development. However, the choice about one side or walking in the street are typical legacies of existing streets built without sidewalks. In many cases this was a result of rural areas transitioning to urbanized development densities and suburban areas not choosing to build sidewalks at the point of development. While a desirable long-term goal for many communities, these past practices make it unlikely that every local residential street will have sidewalks on each side of the street. Because of this physical reality, there is a need for communities to be strategic about their walking network. The need for mapping connectivity of the sidewalk system to provide access to neighboring communities, parks, schools, bus stops, commercial areas, and activity centers is a community planning consideration. Additionally, engaging with the community on where gap filling of sidewalks and where two-sided sidewalks are not going to be provided is an important practice. This may result in mapping of where one-sided sidewalks are planned for gap filling efficiency and where no sidewalks streets may remain (e.g., short cul-de-sacs). Focusing consideration on safe passage of pedestrians is a good starting point.

Why Are Sidewalks Not Built

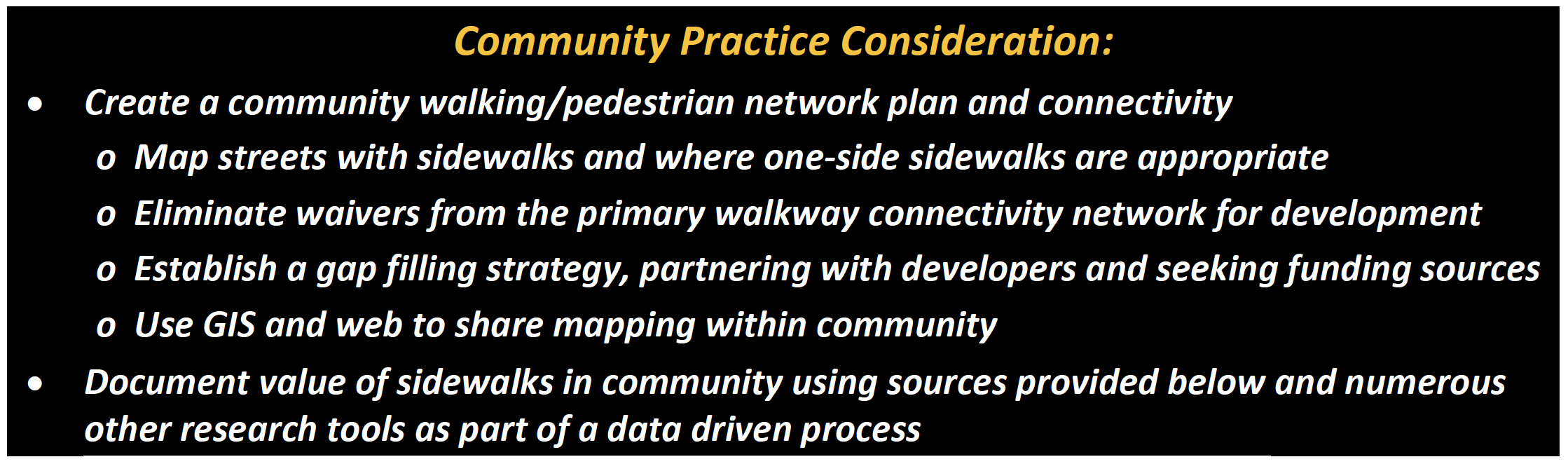

In some circumstances, communities do not know where there are and are not sidewalks. This lack of understanding can contribute to a lack of community strategy for creating walkable neighborhoods and sidewalk connectivity. One of the best places to address this topic is within community transportation plans by including a walking or pedestrian component. Within this plan element, community discussion can occur on topics such as which streets are a part of the walking network and would not be subject to waivers or deferral of sidewalk construction. One of the key aspects of the plan would be mapping of existing sidewalks, planned sidewalks, and future connectivity needs/criteria with development.

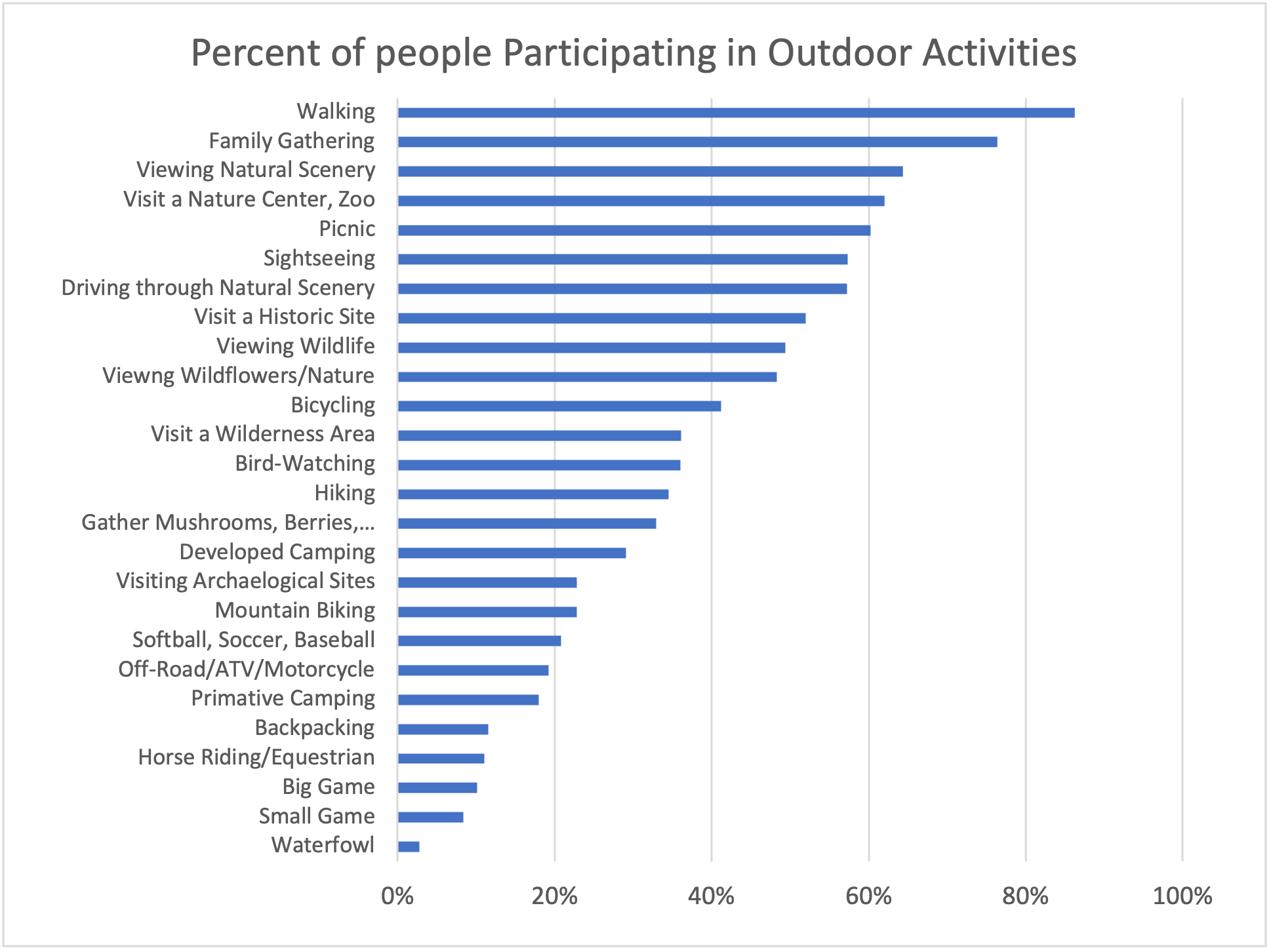

Some neighborhoods have cited in the past that “no sidewalks” provides a “rural” feel or character[8]. This creates an interesting paradox as research and surveys document walking as one of the most popular individual outdoor activities in the USA.[9] Sidewalks are a top response on what improves walking experience.[10] Studies have correlated the increase in Walk Score with increased property value[11]. In some suburbanized areas (particularly wealthier areas), the provision of sidewalks can be viewed as the conversion of typology to a more urbanized culture and environment, creating tension with any plan to add them to the built environment. The “feel” issue could be attributed to perceptions of change or threatening past car-centric lifestyle choices, impacting landscaping placed in public right-of-way, bringing in “other” people, and/or “imposing” a cost on homeowners. It creates an equity issue for communities to openly address. Whatever the underlying reasons, building greater understanding of sidewalks value is needed.

Supporting Resource Information Related to Value of Sidewalks:

http://www.docs.dcnr.pa.gov/cs/groups/public/documents/document/PA_State_Outdoor_Rec_Plan2014_2019_Exec_Summary.pdf

http://www.docs.dcnr.pa.gov/cs/groups/public/documents/document/PA_State_Outdoor_Rec_Plan2014_2019_Exec_Summary.pdf

Leslie, Gretchen, et al., Pennsylvania’s Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan, 2014-2019, Executive Summary, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, page 5.

Percent and number of people 16 years and older in the U.S. participating in land resource-based outdoor activities, 1999-2003.

Adapted from: American’s Participation in Outdoor Recreation: Results from National Survey on Recreation and the Environment, Versions 1-13, USDA Forest Service and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee, 2003, pages 3-4, Table 2.

Estimated Housing Value Gain from Moving to 75th percentile Walk Score from Regional Median

Adapted from: Cortright, Joe, "Walking the Walk: How Walkability Raises Home Values in U.S. Cities, CEOs for Cities," August 2009, page 23, Table 8.

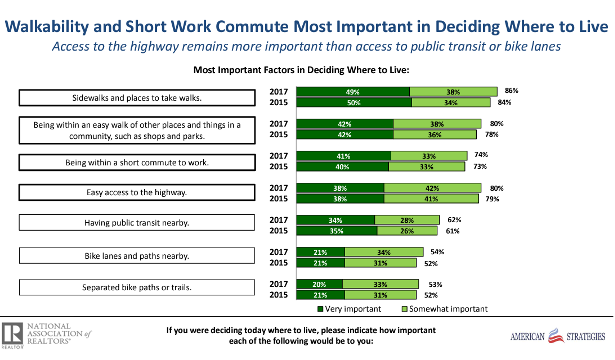

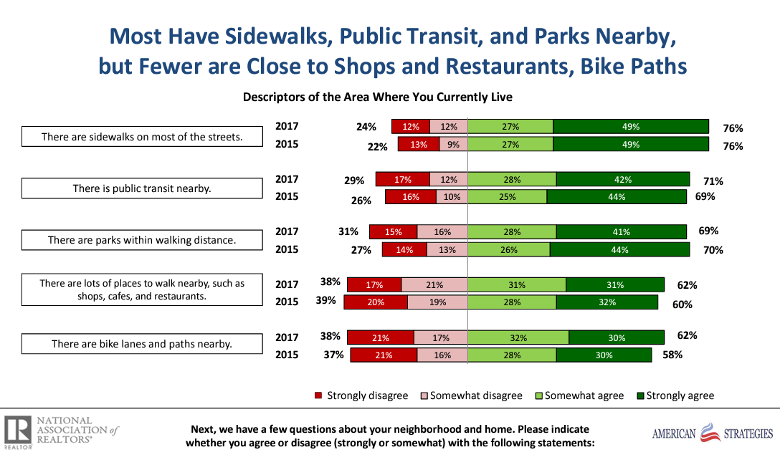

National Community and Transportation Preferences Survey – Executive Summary, National Association of Realtors & American Strategies, September 2017, page 13.

https://cdn.nar.realtor/sites/default/files/documents/2017%20Analysis%20and%20slides.pdf

National Community and Transportation Preferences Survey – Executive Summary, National Association of Realtors & American Strategies, September 2017, page 9.

https://cdn.nar.realtor/sites/default/files/documents/2017%20Analysis%20and%20slides.pdf

A brochure by the City of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin on understanding why the city is investing in neighborhood sidewalks.

https://www.cityofsunprairie.com/DocumentCenter/View/7348/sidewalk_flyer_final

Fronting Sidewalks and Gap Filling

Providing local residential street sidewalks when housing is constructed is a common means of building walking networks. Sidewalk infrastructure investment by homebuilders is a significant investment. For large subdivisions, the density of development lends itself to fronting sidewalk incorporation. For smaller, residential in-fill and major renovation/reconstruction activity, the developer has often not included local residential street sidewalk provision. Gaps in sidewalk networks are difficult to fill after initial residential construction.

Because sidewalks were not built, in many cases it became justification for not building fronting sidewalks in some communities. Agencies developed thresholds to determine if fronting sidewalks should be built (not needed for small development, say fewer than 5-10-15-20 homes being built) or 50 percent or less of the existing streets needed to have sidewalks). In several of these cases the subdivisions scaled their sizes to avoid the cost of sidewalks and then created a circular argument with future development because there are no sidewalks, that they too should not have to build sidewalks.

The cost of building sidewalks has been one reason used to avoid building them at the point of residential construction. Claims have even been made that affordability of housing is impacted by sidewalk requirements. While sidewalk construction can easily be $50-100 per foot ($20-30 per m), it is not out of line with other similar home services such as storm drains, sewers, utilities, driveways, or street width. These are all expensive to home buyers, particularly if they were not built with the house originally.

Early experience (1957) emphasized the need to have sidewalks in place when families move in[12]. This was deemed “more satisfactory” for the owner rather than paying higher taxes later to address sidewalks.

Probably the most important aspects of infill sidewalk planning and programing is engaging the community when identifying the need for local residential street sidewalks. The reality is that many communities have circumstances where sidewalks were not built. Expecting that fronting in-fill development will eventually create a continuous sidewalk leads to many gaps over many years. To address this, communities need to develop pedestrian plans with walkway connectivity network maps to help prioritize where system continuity is a priority. This includes identifying and prioritizing complementary walkability elements such as density, land use mix, and connectivity.

Some attention has been given to making neighborhoods more “social” by using sidewalks; however, some research points out that this is not necessarily a distinguishing attribute of sidewalks[13]. Others opine on car-centric or anti-pedestrian agendas[14] as why fronting sidewalks were not provided when the realities were more likely simply cost-avoidance. Rather than debating subjective considerations, it is best to collaborate with neighborhoods and developers; emphasizing the understanding context, characteristics, and users in achieving plans for sidewalk networks (particularly in-fill and gap filling). This can lead to more productive outcomes.

Sidewalk Width

Many agencies set minimum sidewalk widths based on past FHWA and AASHTO references[15]. However, even in 1999, FHWA noted that a 5-foot sidewalk is “probably wide enough” to accommodate pedestrian traffic and stated that minimum clearance is the narrowest point on a sidewalk. It further notes inaccessible minimum clearance is created when obstacles (such as utility poles) protrude into the sidewalk[16]. This lack of clarity between sidewalk design width and minimum clearance has affected the quality of walking network on local residential streets, particularly in the United States. Because of this, the legacy of “minimum” sidewalk widths as a part of codes, standard drawings or construction details has resulted in a large inventory of bare minimum sidewalk widths for local residential streets. Other countries provide clear direction of 6-feet (1.8m) standards for local residential streets (such as India, Canada).[17]

More recent FHWA documents have updated their recommendations for sidewalk widths but many communities have not reflected these changes. FHWA in their 2013 course materials on bicycle and pedestrian transportation[18] recommended:

“Sidewalks require a minimum width of 5.0 feet if set back from the curb or 6.0 feet if at the curb face. Any width less than this does not meet the minimum requirements for people with disabilities…... 5.0 feet of space is the bare minimum. In some areas, such as near schools, sporting complexes, some parks, and many shopping districts, the minimum width for a sidewalk is 8.0 feet. Thus, any existing 4.0-foot-wide sidewalks (permitted as an AASHTO minimum) often force pedestrians into the roadway in order to talk. Even children walking to school find that a 4.0- foot width is not adequate.”

The actual space needs of the users (refer to question #6 above) should be considered which range from 20 to 48 inches (0.5 to 1.2 m) and commonly are about 27 inches (0.7 m). Canada notes tricycle use as another criterion (tricycles are about 30 inches wide or 0.75m). To allow adequate space for two-way traffic on a sidewalk including minimal shy distances would require:

|

27 inches (average of all user needs) x 2 (two-way) + 24 inches of collective shy distance between humans and to each edge) = 78 inches or equal to ~6 feet sidewalk + 6-inch curb (2 meters) |

Sidewalk width and minimum clearance or pedestrian access route (PAR) should not be conflated. Sidewalks width is the standard plan for construction of a sidewalk. Minimum clearance or PAR are conditions which occur on sidewalks due to features that are built and physical features that constrain the environment in which the sidewalk is placed. Think of this like a “road narrows” condition where 12-foot lanes are used for vehicles on roadways. The lane width returns to the basic lane width after the narrowing feature.

The concept of adequate space for pedestrians has been understood for some time. Work conducted by Pushkarev/Zupan[19] and Fruin[20] in the 1970s and 1980s provided similar research and analysis documenting the need for adequate walking networks to encourage frequency of use. A change for many communities to 6-foot (1.8 m, behind the curb) walkways on local residential streets would represents a significant change from their current practices. The task force considered this and strongly believes change is needed to clarify the misconceptions of minimum clearance and minimum sidewalk width in design practice.

When considering roadway designs for local residential streets, vehicular space has routinely been accommodated well beyond the minimum clearance. Vehicles are commonly less than 6 feet wide and the widest vehicles 8 feet wide. The right-of-way devoted to vehicle space would not be as large if it were designed the same way as the sidewalks are for many communities who use 4 feet. The example would be for cars to go off street to pass each other, the equivalent of having a pedestrians step into the street to pass each other (assuming they actual could access the street, due to curbs). Simply stated, to improve community practices for greater walkability and safe passage for pedestrians to pass each other, encourage walking, change to agency design standard drawings, and codes for local residential street sidewalk widths require updated consideration.

|

Case Examples: City Standard Details There are several agencies that use 6-foot (1.8 m) sidewalk width. BART Multimodal Access and Design Guidelines, (Oakland, CA: Bay Area Rapid Transit, August 2017), Table 1, page 23. https://www.bart.gov/sites/default/files/docs/BART%20MADG_FINAL_08-31.pdf Street and Site Plan Design Standards, (Chicago, IL: Chicago Department of Transportation, April 2007), Table 1, page 5. https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/depts/cdot/StreetandSitePlanDesignStandards407.pdf Standard Construction Details - Shared Use Path & Sidewalk, (Willington, DE: Delaware Department of Transportation, December 2021), Standard Number M-3(2021). https://deldot.gov/Publications/manuals/const_details/index.shtml?dc=2021 Transportation Engineering Manual, (Fort Worth, TX: Transportation and Public Works Department, June 2019), Table 5-2, Page 5-6. https://www.fortworthtexas.gov/files/assets/public/government/documents/transportation-engineering-manual.pdf Standard Details and Drawings: Sidewalk, (Portland, OR: Portland Bureau of Transportation, April 2019), Standard Drawing Number 551. https://www.portland.gov/transportation/engineering/documents/p-551/download Standard Plans for Municipal Construction, (Seattle, WA: Seattle Public Utilities, February 2020), Standard Plan Number 420. https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/SPU/Engineering/2020_Standard_Plans.pdf Standard Detail Drawings – Residential Sidewalk, (Vancouver, BC: Engineering Services, September 2018), Drawing Number C1.1. |

Sidewalk Design, Construction, and Maintenance: A Best Practice by the National Guide To Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure, (Ottawa, ONT: Federation of Canadian Municipalities and National Research Council, July 2004), 10.

This best practice recommends a minimum sidewalk width of 1.5 m. When the sidewalk is located adjacent to the curb on major roadways, the width should be increased to 1.8 m. The preferred width to provide for the safe passage between an adult and a person pushing a baby carriage or in a wheelchair, or a child on a tricycle is 1.8 m.

Sidewalk Paving Surface

Most agencies build sidewalks with concrete. Asphalt has been utilized; however, the task force noted that asphalt sidewalks may lack a “differentiated space” for pedestrians which may lead to unintended consequence of use by bicyclist and/or parked cars.

Street Lighting

The survey identified that most communities provide residential street lighting.

Sidewalk Buffer

While buffer space for local residential street sidewalks provides desirable pedestrian experience, it is not the only solution for residential streets. The choice between curb-tight and buffered sidewalks on local residential streets is not likely to be uniform or one way. When HOAs exist and provide maintenance, the buffer option works well. However, many times without the HOA, the landscaping in the buffer areas can be under maintained. That is expressed in the question regarding requirements for buffered or curb-tight sidewalks. The largest response was for separated buffer space but it was nearly equal to the “either” option. The lowest response was for curb-tight as a requirement.

Curb tight sidewalks can provide convenient access to on-street parking, minimize the impact of poor landscape maintenance on sight distance at intersection corners and reduce right-of-way dedication. Landscaping afforded in a buffer can be provided on the property side of the sidewalk where the homeowner can more readily install and maintain it, providing similar shade/aesthetic qualities (see below).

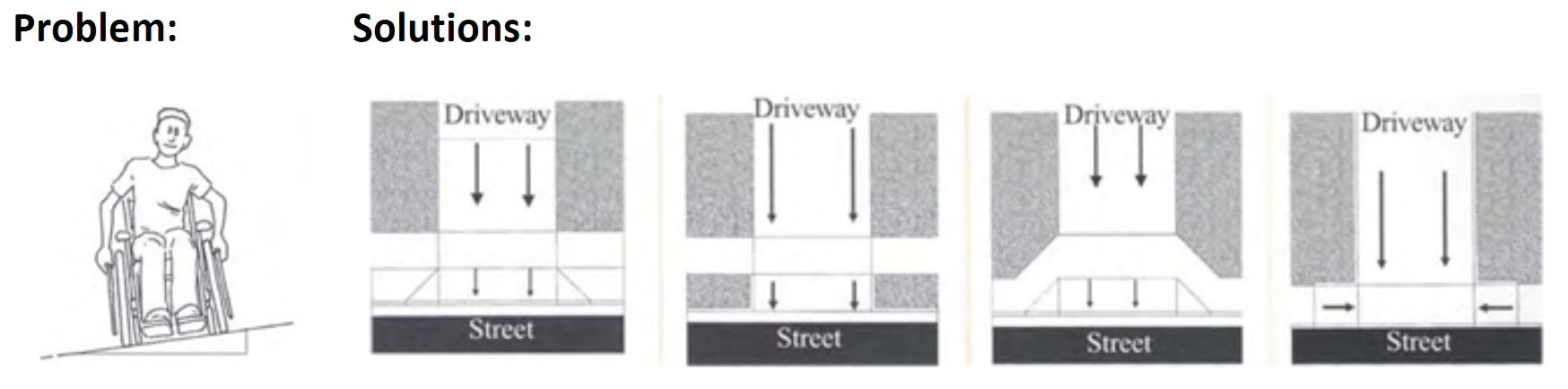

The frequency of driveways can play a role in the selection between buffered and curb-tight sidewalks. When driveway frequency becomes 50 feet (15 m) or less, the occurrence and frequency of pedestrians travelling down and up driveways makes buffered sidewalks superior given its level sidewalk. Curb tight sidewalks need to use ADA slopes (1:12) for driveway transitions unless the curb tight sidewalk is widened enough to provide level a sidewalk space behind the driveway curb cut.

The use of driveway density/frequency as a criterion for planning sidewalk buffers can help clarify where the curb-tight sidewalk option can be applicable and where they are not appropriate. It is not essential that sidewalks for local residential streets be provided in one fashion, even on one street. Communities can set policy for this design option as they see it best suiting their context, characteristics, and users.

Triggers for Maintenance

The survey clearly noted a reactive/complaint basis that many agencies use toward maintenance of local residential street sidewalks. Opportunity exists for improved (proactive) community services using existing and emerging technologies and policies. One recent policy concept which aligns maintenance and repairs with proactive action is using the point of home sale as a means to fund repairs/maintenance as the proceeds from the capital gain are available at that time. This idea can be helpful to address equity issues associated with user pays costs[21] assigned to homeowners (which is done in many cities and states in the USA).

Avoiding Obstructions

This seems to be an obvious practice of design and construction – do not block or place barriers in a sidewalk. However, it is all too common the case that sidewalk blockages occur. This is unlike the street space where obstructions rarely occur.

Most jurisdictions have detailed sidewalk standard drawings and details that specify minimum widths of sidewalks. However, the details for other street features such as light poles, utility poles/bungalows, fire hydrants, mailboxes, and street signs do not cross reference to the standard sidewalk detail. And now with electric vehicles, addressing the impact of charging cords or charging stations create a new consideration. These items can end up being placed in the sidewalk without consideration of minimum sidewalk width – many times resulting in obstruction. This could be as simple as a standard note on all other standard drawings referencing the sidewalk detail and specifying minimum clearance requirements (for example, locate in buffer area, behind sidewalk or widen sidewalk to appropriate width at obstruction). Having mapped existing, planned, and future sidewalks allows the routine maintenance and replacement of these features to be done in a manner compatible with maintaining minimum sidewalk widths.

These obstruction may occur as many water, fire, electrical, lighting and utility (telephone, cable, etc.) districts do not deal with public works or standard drawings. Because of this, they may be unaware of the needs or conduct their work in the least cost manner without regard to other agencies (silos). In particular, mailboxes (in the USA) involve the Postal Service which is a federal agency. As the USPS has sought more group mailboxes, having the USPS understand sidewalk clearance needs within the community requires substantial coordination.

In all cases, these obstructions can be planned as they are common services for a street. Placing obstructions outside the sidewalk spaces (in buffers or behind the walk) or adding space to the sidewalk outside the obstructions are best practices that can be planned for and designed properly prior to permits and construction.

Three other common obstruction issues that merit attention are garbage cans, parking and discontinuous sidewalks that end (not continuous). Key issues for each include:

- Garbage cans – many urban waste management organizations are using robotic systems for garbage pick-up. Because this is likely the common future operation, rolling carts that are 2 to 3 feet (0.6 to 1 m) wide will be common and if placed on the sidewalk, they consume much of the walkable pathway. To avoid obstruction garbage carts can be placed in the street. Where they cannot be placed in the street, the sidewalk design can include a small 3-foot wide (1 m) extension of the driveway (roughly 10-feet (3 m) long) in the “buffer zone” parallel to the street which can be used to place garbage carts without sidewalk obstruction.

- Parking – This issue becomes problematic with inadequate parking supplies and narrow streets which cannot appropriately accommodate on-street parking. Vehicles use driveway aprons to access the sidewalk and then park on it, blocking passage. To address this obstruction, it is possible to plan for right-sized parking supplies and street widths appropriate for on-street parking. Common local residential streets of 28 to 32 feet (8.5 to 10 m) can serve this purpose.

- Discontinuous sidewalks – where the older neighborhoods do not have sidewalks and the provision of sidewalks has come with in-fill or small subdivisions, gaps in the pedestrian walking network can be common. Where these sidewalks end and how they transition can make the interim “gap” condition more manageable. Some examples include:

- Extending the new sidewalk to the nearby (within 50 to 150 feet) sidewalk, filling the gap. This can be done with concrete or asphalt.

- Extending the new sidewalk from fronting in-fill development to the immediately adjacent driveway allowing for access to the street via the existing driveway apron; or

- Building a curb ramp/ramp from the sidewalk to the street, addressing proper drainage. This typically involves a barrier at the end of the new sidewalk in addition to the ramp.

Sidewalks at Driveways

The Public Rights-of-Way Access Advisory Committee recommends that the PAR[22] elevation across the driveway be maintained (sidewalk high) and the driveway slope to the street is outside the walking area[23]. Only for conditions where the space between the curb and the back of right-of-way is not large enough to accommodate this design (noted as commonly below 8 feet (2.4 m)) should the sidewalk ramp down (depressed) to address the driveway transition. The number of these transitions should be managed in pre-existing conditions and minimized in new design (refer above to sidewalk buffers regarding average driveway density less than 50 feet (15 m)).

Prior to the last two decades, it was common practice to slope a curb-tight sidewalk through the driveway apron toward the gutter. This prior practice creates significant transverse sidewalk slopes in the driveway apron area:

- With a 4-foot (1.2 m) sidewalk = 11% slope

- With a 5-foot (1.5 m) sidewalk = 9% slope

- With a 6-foot (1.8 m) sidewalk = 7.7% slope

Leverson Boodlal, Accessible Sidewalks and Street Crossings – an informational guide, FHWA-SA-03-019 (Washington, DC: FHWA, 2004), 10 (Figure 4) & 18 (Figure 15). Note: this document also refers to a minimum pedestrian zone of 6 feet (page 8). https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/16137

A transverse-sloped sidewalk of this nature does not meet ADA accessibility. For these reasons full width, parallel (depressed) sidewalk transitions to driveways have been used with the transition lengths of about 6 feet (1.8). This results in an 8.3 percent slope running slope (not transverse) when 6-inch (0.15 m) curb heights are used.

It should be emphasized that it is not only for ADA but for all pedestrians, particularly in areas that experience snow and ice. As shown below the transverse slopes can lead to slip/fall in icy conditions and can produce potential for tripping near the curb when the transitions are short (sometimes as little are 3 feet (1 m)).

This task force focused on exploring one aspect of sidewalks – the aspect associated with local residential streets. The survey of practices for local residential street sidewalks highlighted several areas that communities may consider regarding current practice as they develop walking networks and pedestrian plans. This includes reviewing standard drawings and details for minimum sidewalk widths and clearance. Other references should also need to be reviewed to provide consistency between design guides as agencies consider updates to their standard drawings and details. For example:

NACTO Urban Street Design Guide, October 2013

“Critical: Sidewalks have a desired minimum through zone of 6 feet…..”

Comment: The term ‘through zone” is used which is not the full width of a sidewalk. Three additional areas contribute to the width of a sidewalk (the frontage zone, street furniture zone and enhancement zone). This can create confusion when creating standard drawings and details with a foundational minimum sidewalk width.

AASHTO Guide for the Planning, Design and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities, 2nd Edition, December 2021, section 3.3.4, page 3-14

"It is recommended that a sidewalk (or the portion of sidewalk that functions as the pedestrian zone) be at least 5-feet (1.5 m) wide, provided that a buffer is present between the sidewalk and the edge of the roadway. A 6-foot (1.8 m) width (exclusive of the width of the curb) is recommended where sidewalks are located immediately adjacent to a roadside curb.”

Comment: The requirement of local residential street minimum sidewalk widths of 6-foot behind the curb for curb-tight sidewalks is consistent with Community Practice Considerations noted above.

AASHTO A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 7th Edition, 2018, section 4.17.1, page 4-65

"Sidewalk widths in residential areas vary from 4 to 8 feet (1.2 to 2.4 m). Sidewalks less than 5 feet (1.5 m) in width require the addition of a passing section every 200 feet (60 m) for accessibility……..Where sidewalks are placed adjacent to the curb, the widths should be approximately 2 feet (0.6 m) wider than the minimum required width.”

Comment: The requirement of local residential street minimum sidewalk widths of 6-foot behind the curb for curb-tight sidewalks is consistent with Community Practice Considerations noted above.

The intent of this summary is to expand the discussion about sidewalks and share an understanding of sidewalk practices. After sharing this summary, it is possible that ITE membership may wish to further the exploration and advance products such as an informational report and/or recommended practice. That would involve more engagement with membership and volunteers. Additionally, there are other sidewalk categories that could also benefit from further reflection including those related to:

- Collector and arterial streets

- Commercial/business zones

- Bridges, interchanges, and underpasses

- Trails and pathways

- Others raised by the profession

If you have interest in these topics, please feel free to raise them to the Pedestrian/Bicycle Committee of ITE under the Complete Streets Council. Task forces may be created to advance more sidewalk topics.

Local Residential Street Sidewalk Task Force

Of the Pedestrian/Bicycle Committee of the ITE Complete Streets Council

Randy McCourt (Chair), Josie Ahrens, Jennifer Butcher, Emmeth Duran, Joshua Harris, Jen Malzer, Dale McKeel, Kendra Miller, Peter Truch, Patrick Wright

Pedestrian/Bicycle Committee (Chair: Claude Strayer)

Complete Streets Council (Chair: Alex Rixey)

[1] City of Los Angeles, Safe Sidewalks LA (Los Angeles, CA, 2021). https://safesidewalks.lacity.org/

[2] Tom Huber et al., Guide for Maintaining Pedestrian Facilities for Enhanced Safety (Washington, DC: FHWA-SA-12-037, October 2013), 12.

[3] Kara Macek, Spotlight on Highway Safety: Pedestrian Traffic Fatalities by State, Preliminary Data 2021 (Washington, DC: Governors Highway Safety Association, May 2022), 20.

[4] VTTI/VHB, Pedestrian Lighting Primer FHWA-SA-21-087 (Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration Office of Safety, April 2022), 20 (Table 2).

[5] ANSI/IES RP-8-18, Recommended Practice for Design and Maintenance of Roadway and Parking Facility Lighting (New York, NY: Illuminating Engineering Society, 2018), 11-6.

[6] AARP, Tips, Tools and Resources for Organizers - Sidewalks and Streets Survey (Washington, DC, AARP, July 15, 2020). https://createthegood.aarp.org/volunteer-guides/walkability-survey.html

[7] Walkscore is public access walkability index that assigns a numerical walkability score to any address in the United States, Canada, and Australia. www.walkscore.com

[8] What are some of the reasons that some people don’t want sidewalks, https://www.pedestrians.org/retrofit.htm; and Matt Hickman, Sidewalk Hate Runs Deep in Some Suburban Neighborhoods (New York, NY, Treehugger, May 30, 2018). https://www.treehugger.com/some-suburban-neighborhoods-sidewalk-hate-runs-deep-4868176

[9] USDA/University of Tennessee, Forest Service, American’s Participation in Outdoor Recreation, 1999-2002 National Survey of Recreation and the Environment (Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture/Forest Service, 2002), 1. Survey of over 57,000 people, top response (86.2% walking). https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/trends/Nsre/Rnd1t13weightrpt.pdf

[10] Roy Gothie, Active Transportation Plan – Statewide Survey (Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, 2019), 11. Of 12,780 responses, “more sidewalks” was the top response to the question of which of these changes would most improve your walking experience?http://files.dep.state.pa.us/Energy/Office%20of%20Energy%20and%20Technology/OETDPortalFiles/Climate%20Change%20Advisory%20Committee/2019/12-10-19/2019_CACC_Active_Transportation_Plan_Presentation.pdf , and AAPR, Sidewalks: A Livability Fact Sheet (Washington, DC: Walkable and Livable Communities Institute, 2014). https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/livable-communities/livable-documents/documents-2014/Livability%20Fact%20Sheets/Sidewalks-Fact-Sheet.pdf

[11] Cortright, Joe, Walking the Walk: How Walkability Raises Home Values in U.S. Cities (Chicago, IL: CEOs for Cities, August 2009), 23. (https://nacto.org/references/cortright-joe/); and Lily Katz, How Much Does Walkability Increase the Value of a Home (Seattle, WA: Redfin News, October 14, 2020), 1. (https://www.redfin.com/news/how-much-does-walkability-increase-home-values/)

[12] American Planning Association, Sidewalks in the Suburbs – Information Report #95 (Chicago, IL: American Society of Planning Officials, February 1957), 18.

[13] Samuel Abrams, Do Sidewalks Make Us More Social? (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, December 3, 2021). https://www.aei.org/op-eds/do-sidewalks-make-us-more-social/

[14] Malcolm Kent, Is there any reason not to have a sidewalk? (Washington, DC: Greater Greater Washington, January 15, 2015). https://ggwash.org/view/37058/ask-ggw-is-there-any-reason-not-to-have-sidewalk

[15] FHWA-HRT-05-101, University Course on Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation Lesson 9 (Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration, July 2006), 2. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/safety/pedbike/05085/chapt9.cfm

[16] Barbara McMillen, et. al., Designing Sidewalks and Trails for Access - Part I: Review of Existing Guidelines and Practices (Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration, July 1999), 36-37 and page 4.4, Table 4-1.

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/publications/sidewalks/sidewalks.pdf

[17] Kama Koti Marg, Guidelines for Pedestrian Facilities IRC:103-2012 (New Delhi, India: Indian Roads Congress, May 2012), 8. (Table 2, minimum obstacle free walkway width and Residential areas = 1.8 m (6 ft).

[18] FHWA, Course on Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation – Chapter 13 (Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration, February 2013), 1. https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/PED_BIKE/univcourse/swless13.cfm

[19] Boris Pushkarev and Jeffrey Zupan, Urban Space for Pedestrians – A Report of the Regional Plan Association (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1975).

[20] Jeffrey Fruin, Pedestrian Planning and Design (New York, NY: Metropolitan Association of Urban Designers and Environmental Planners, 1971).

[21] Donald Shoup, Fixing Broken Sidewalks (Los Angeles, CA: Access UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies, Spring 2010, Number 36), 30-36.

[22] PAR – pedestrian access route is a continuous and unobstructed path for pedestrians to navigate along the sidewalk, driveway, curb ramps, crossings, and pedestrian facilities that is fully accessible.

[23] Hilberry, Hilton, Prosser, Chapter 5 – Model Sidewalks of Special Report: Accessible Public Rights-of-Way, Planning and Designing for Alternations, (Washington, DC: U.S. Access Board, July 2007). https://www.access-board.gov/prowag/planning-and-design-for-alterations/